[ad_1]

DOHA, Qatar — Seeing Is Believing: The Art and Influence of Gérôme reifies an Orientalist view of the Eastern world as undeveloped before attempting to dismantle that perspective. Its three curators — Emily Weeks, Giles Hudson, and Sara Raza — beckon viewers to reconsider the aesthetic legacy of Jean Léon-Gérôme, an artist infamous for his mythicized depictions of the people and customs of the region.

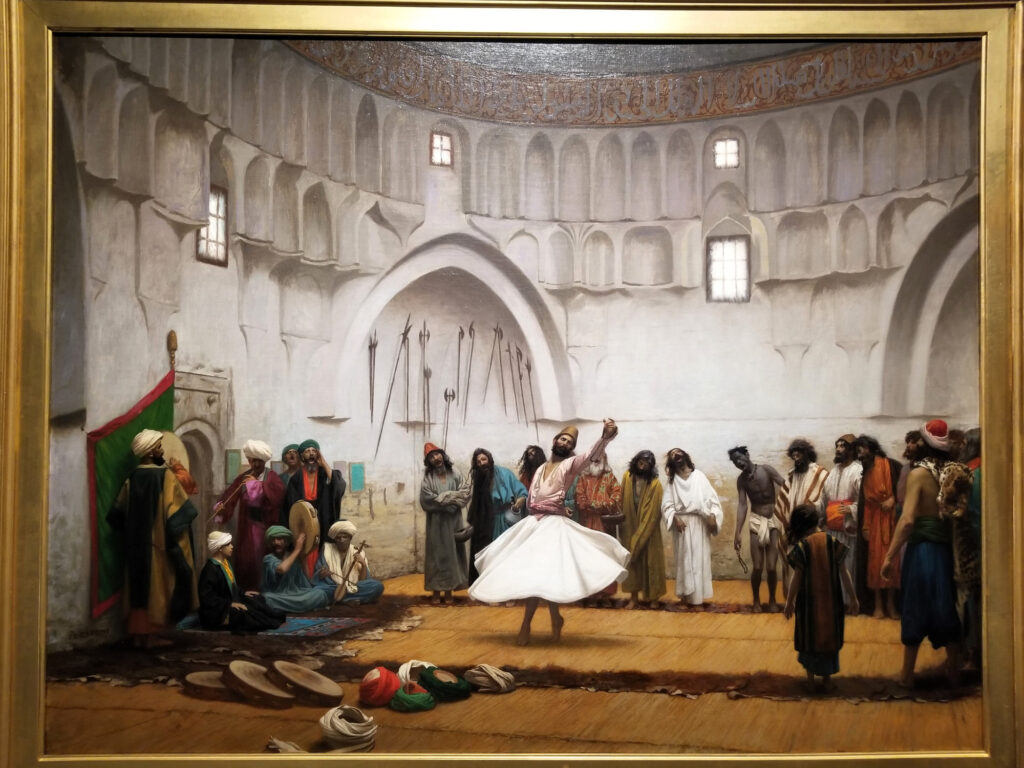

On cerulean walls and under warm, dim lights, the first section presents an unsophisticated definition via wall text: “The term ‘Orientalism’ describes how artists from outside the MENASA region… depicted its peoples, cultures, and landscapes, often blending reality with fantasy.” It’s a clever curatorial choice not to include works oversaturated with art historical opinion, such as Gérôme’s notorious “Snake Charmer” (c. 1879) or smutty paintings of enslaved North African people in paintings such as “The Slave Market” (1866). In this absence, we can focus on other works, such as the gracefully drawn portrait of the poker-faced “Veiled Circassian Lady” (1876) — depicted wearing Turkish fabrics and seated against Persian rugs — and see clearly that these also tell lies. Though Gérôme titled the painting after a Turkish ethnic group, implying that he met her on his travels, he in reality hired a fair-skinned model in Paris to pose for him, projecting his fantasies onto the canvas.

Weeks educates viewers both about Gérôme’s artistic processes, such as bricolage — a technique of layering visual details and ideas from a variety of sources — and criticism of the West’s salacious depictions of Arabs in the wild, mosques, or gun shops by scholars like Edward Said and Linda Nochlin. Regarding what the exhibition calls, via wall texts, his “famous style,” the section presents both sides of Gérôme — the adept painter and the fantasist. However, the scrupulous curatorial emphasis on Gérôme’s artistic prowess and peer influence outweighs the presentation of criticism directed at him. The exhibition materials premise Gérôme as a “chronicler of modern cultures and peoples of North Africa and Middle East,” with “fancifully imaginative and faithfully naturalistic” views. I sense apologetic hints that Gérôme and his contemporaries like Eugène Delacroix deserve a second look for the virtuosity of their photorealism. I don’t take the bait.

Stepping into the second section of Seeing Is Believing feels like entering a different exhibition. Here, a plethora of early modern regional images show that European photographers from Gérôme’s circle superimposed tone and color to depict an exotic and unfaithfully extravagant East. Hudson counters this woeful narrative via Persian photographer Naser al-Din Shah’s realistic images of the Qajar court’s harem, which are less staged and ornamented. (“Harem” (2009), a video work by artist Inci Eviner, was removed from the show on opening day at the request of Qatar’s Ministry of Culture.)

Brighter and roomier, the third section displays international modern and contemporary art opposing Eurocentric othering. Works by artists like Aziza Shadenova and Baya Mahieddine disrupt the voyeuristic European gaze through semi-abstract figures and patterns that resist essentializing. Nadia Kaabi-Linke’s installation “One Olive Garden Tree” (2024), for instance, is a stunning maze of cut olive trees, representing ongoing colonial expansion in the Levant. Raza’s curation in this section is anything but impartial, a necessary corrective and a gorgeous conclusion.

Gérôme, frankly, is troubling. His oeuvre will always remind me of the West’s sordid stereotyping and imperial projects against the people of Africa, South Asia, and the Levant. Seeing Is Believing reinforces the fact that Gérôme’s was a distorted Westward gaze that we need to continue to deconstruct. In lengthy shows like these, I prefer conserving most of my energy for anti-Orientalist global expressions. Here’s a wild idea: What if we curate reverse chronologically, with viewers encountering the full complexity of MENASA art before seeing Gérôme et al.’s narrow perspective? That way, we can see their vision for what it really is — regressive.

Seeing Is Believing: The Art and Influence of Gérôme continues at Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art (Education City Student Center, Doha, Qatar) through February 22, 2025. The exhibition was organized by the Lusail Museum and curated by Emily Weeks, Giles Hudson, and Sara Raza.

[ad_2]

Source link